“If you could wake up tomorrow and have everything be perfect,” my new therapist asked yesterday, “what would be different?” I had to think for a minute. I’m generally happy with the way things are. But she said that my job was to wake up in a perfect world and describe that to her, and once I have a job, I take it seriously.

I listed the things I’m sure everyone does: I moved my Midwestern life to LA, including all the people I love and work with; I doubled my salary (and really, should have tripled it, this was a dream exercise); I moved people I love closer to me, geographically; and then I said, “Oh. And Prodigal Son wouldn’t be cancelled.”

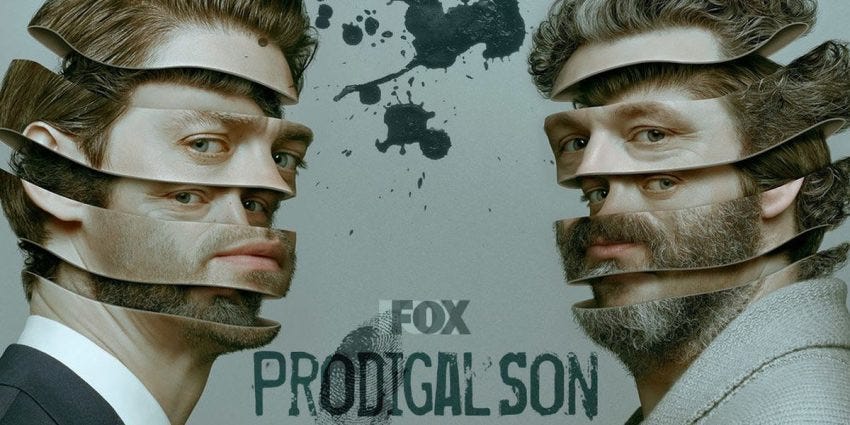

I’d gotten the news of its cancellation a few hours before this appointment with a new doctor, someone I was seeing in the wake of real world trauma that happened in my life last week— on Wednesday, or what I call “Prodigal Sonday,” which is an actual calendar day for me. (I have to wait until it is on Hulu the day after it airs on Fox, but it’s worth it.) Last week, the only way I was able to move from The Incident back into Normal Life was through watching the third-to-last episode this season. I’ve grown to love everything about the show: it’s a true ensemble, each actor so strong that every scene is elevated, despite most of the plot following Tom Payne’s brilliantly-embodied Malcolm Bright (née Whitly). I find myself, fairly often, drifting into the grey-tinted New York of the series: I wonder how Edrisa, JT, or Dani are doing or worry over Jess Whitly trying to write a book about her life. Michael Sheen, who plays Malcolm and Ainsley’s father Martin Whitly (who is also the serial killer “The Surgeon”), has reignited a passion for acting in me, and his triumph and joy even while playing a terrifying predatory narcissist has altered everything from my mood during “these unprecedented times” to the way I say the phrase, “My boy/girl!” I’ve even been on and off suspicious of Ainsley Whitly since far before the last season’s big reveal (and this season’s bigger ones). But perhaps the biggest problem for me (outside of Sheen being so charming that someone is planted in every episode to remind the viewer that he killed 23 people) has been Gil Arroyo and the way he selflessly loves— well— everyone.

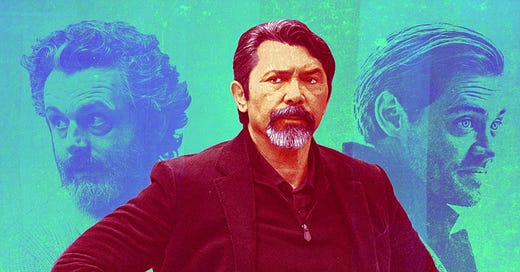

One of the catalysts for the action of the show is that when Malcolm was 11 years old, he pieced together enough of what his father was doing to call the police. When the young beat cop, Gil Arroyo (Lou Diamond Phillips), showed up, Malcolm quietly warned him that Martin often poisoned people with tea— and he’d just put some on. Malcolm saves at least one life that night, and the implication is that he was likely the only person with the power to intervene and stop his father. Eventually, Malcolm changes his last name to ‘Bright’ while the rest of the Whitlys stubbornly stick it out, despite the baggage the name carries. By the time the show is in present day, Malcolm is in his early 30s and has recently lost his job with the FBI— and he goes home to New York, where now-Lieutenant Gil Arroyo brings him in as a consulting profiler.

Don’t get me wrong. Malcolm is intriguing. He has a keen eye for how to listen and react instead of just acting on the lines of dialogue he’s been given, and he’s exceptional at not telegraphing his physical movements even when they are outrageous (he’s come out of more than one third or fourth floor window; he sleeps shackled to the bed because of violent night terrors; he’s used an ax to cut off people’s hands; these are all things he does in the name of justice and maybe a little bit of fun, most of which in the first or second episode). The interplay between Payne and Sheen is worth price of admission: there is no “Spy Vs. Spy” more intense than two people who are both above a genius level IQ trying to guess what the other will do first, especially because, no matter how bad things are, no matter how much Malcolm wants to deny it— they love each other. He doesn’t want something bad to happen to his father. And though he may be bad at any kind of recognizable love, it’s undeniable that Martin loves his son the best way he can. One of the first lines we ever see him deliver is to his then 11-year-old as he’s arrested: “We’re the same, you and me.” There is no more threatening line from a narcissist, but also no more affirming one: when the narcissist recognizes their self in an “other,” the bond is stronger.

I cried when I heard the show was cancelled. I’ve been upset about cancellations before. I was an Arrested Development diehard (that one is also on you, Fox); in college, I mourned the cliffhanger ending of Veronica Mars. More recently, I was devastated by the cancellation of Speechless, a comedy that starred a young man with cerebral palsy. As a woman who had a stroke at 31 and has been on a cane ever since, I can say without a doubt that the way J.J. Dimeo’s family adapted and overcame on Speechless was unique and gave me a touchstone. So why, all the sudden, is a crime procedural I haven’t known as long ripping me up so much? I assumed it was the pandemic. Maybe it was because this was my crutch, I rationalized.

I couldn’t sleep the night I heard, and in my dimly-lit room, it hit me. It wasn’t the pandemic. It wasn’t the brilliant writing or acting. It was 100% Gil Arroyo. I was going to miss him. Or weirder— I was going to miss the part of me that felt most alive and thrumming while Phillips was onscreen, the part that felt like someone else loved the same way I did. In all the other shows, I saw parts of me represented— but in Gil? It was like I hoped I would somehow become a better person by somehow understanding the way he loved intuitively. If life is marked by finding the stories that help turn us into the better people we want to be, Prodigal Son makes my short list.

*

From the time Malcolm is 11 until he takes the consulting job with the NYPD, he keeps in touch with Gil. In fact, Gil steps in and becomes a father figure to the extent that, at one point, it’s revealed that he and the former Mrs. Jessica Whitly considered dating, but thought it unfair because Malcolm needed him so much. Gil later married a woman, Jackie, and in the years the show doesn’t cover, it is implied he lives a full and beautiful life with her (that was, I’m sure, perfect, except he would likely move to LA, triple the salary, and uncancel the show). He doesn’t, however, have kids. He never stops checking in and checking up on Malcolm, though. His responsibilities to Malcolm end at the door— he doesn’t have to ever check on him again, and really, Gil’s life might have been easier. But in the scene where Martin Whitly is arrested, a few things happen: young Gil Arroyo realizes that a child has saved his life; he becomes a celebrity for arresting a man guilty of killing at least 23 women; and he bends down to the young boy, whose life is in chaos and about to get a whole hell of a lot worse, and he hands him a hard candy.

Malcolm is rarely without candy for the rest of the series. Really, he barely knows how to feed himself or survive, but there’s always licorice and hard candy. The callback to that first devastating moment is palpable, and every time Bright pulls out inappropriately timed suckers at gravesites, Arroyo seems to both roll his eyes and try to hide his smile. He knows Malcolm is not his kid. Malcolm is hyper-aware of who his father is. And yet, the pull to love a child with no biological imperative can be so strong— and isn’t something I’ve seen done half as well, even in shows about stepfamilies. I would know. I’m a stepmom whose stepdaughter spends all but Monday evening and every other weekend with her dad and me. She has two parents who love her dearly, and I know that in the plan they both had for her life, I didn’t exist. No one brings a baby into the world hoping that they’ll be able to provide a good stepparent. In fact, when my stepdaughter was younger, I would watch the faces of the other parents on field trips as they found out I was “just a” stepmom: it was so much worse that I was there and I loved her. There was nothing more threatening than a non-parent who was enthusiastic and loving.

OK. Now imagine you can’t have kids. (That’s my subtle way of telling you that I can’t.)

I don’t know if Gil and Jackie could have had kids before she got sick, but they didn’t— and despite Malcolm’s seeking attention and love from his father, Gil stayed in the loop. He loved boundlessly, expecting nothing in return. He watched Malcolm grow up. He got him a job. He took care of Malcolm’s mom, Jess, when she needed it, even after she rejected him romantically and they were both single again. He never created a dichotomy in which Malcolm would have to choose between him and his father. He never even asked for love in return, though there are several scenes in which you can see the unspoken bond between them. The closest the show has come (so far: I guess there are two 47 minute episodes left) shows Gil talking to Martin with absolute disdain— not because he’s jealous of the relationship the serial killer has with his son, but because he’s furious someone could have a son as amazing as Malcolm and then use him as a Machiavellian puppet.

I recognize the way Gil loves almost everyone on the show, though: his big love for Malcolm is loud and beautiful, but he knows to keep it understated as not to rub up against Malcolm’s communication style too much. Malcolm isn’t the only “kid” he winds up taking on, though; he picks up strays everywhere he goes. I’m a college professor. If you want to talk about loving kids who are Definitely Not Your Kid, do I have the job for you. Parents send me their already-adult children, and I immediately begin to, as a creative writing professor, learn things about them that are lovable and beautiful and scary and sad. I stay up at night worried about them. I see them when I’m on vacation and stop in cities they live in. I talk to them on Zoom long after they graduate. On one occasion, I was so anxious about a student graduating that I wrote a seven-page poem about not knowing what to do with the love that, I theorized, would not just evaporate upon graduation. (It didn’t, but I got lucky and the student stayed in contact.)

Which is why as the series goes and it became clear that Gil stepped into the “parent-but-not” role with more than one person who works for him, I grew more attached. Detective Dani Powell, who had become addicted to drugs doing undercover work, is tightly bonded with Gil from the start; she eventually shares that Gil is the one who pulled her out of the operation, who sent her to rehab, and who got her a job at Major Crimes once she got back. Dani is old enough when Gil ‘adopts’ her that she doesn’t need a parent— but she does need help. And perhaps that’s the part of Gil that is aspirational to me: I always want to be able to love deeply. I want to be able to help— and I want to be action-oriented about it. “You’re a solutions person,” my new therapist said yesterday after I told her about The Incident. (Does it matter if I tell you that it was something that happened to a student of mine? A student, I suppose it goes without saying, I love?) In my better moments, I am a solutions person. I’m someone who can love big and not ask for anything in return. In fact, I have said to more than one person in my life— “You don’t need to say this back, but I love you.” As far as I see it, it’s more important for a student to know that than it is for me to feel some kind of validation. They didn’t ask for me to love them. If that comes naturally? They should know how lovable they are.

It hurts Gil, sometimes. The season one finale is a spectacle of ways Gil is hurt by his association with the Whitly family and the people he loves. Early in the second season, he helps one of his detectives pursue and then decide whether or not to keep pursuing a deeply personal assault. Gil rarely gets to date who he wants, be with who he wants, spend time with who he wants— and if you’ve watched the show, you know— he doesn’t even usually get to drive what he wants. This is a man who likely never gets a Father’s Day card (though I’m not imagining Bright is sending brightly colored construction paper to his father, the serial killer, either). And what I’m going to miss the most about Prodigal Son?

Lieutenant Gil Arroyo didn’t need any of those things to be happy. His life is more than enough as it is: helping solve crimes, loving the people in his life as hard and as well as they are willing to let him, and creating space for people who, otherwise, would lead very lonely lives.

*

I know it’s self-centered to write an essay about how great a character is and then say that I see myself in that character, but know— so much of it is aspirational for me. I know in my best moments I could rise to the occasion of being like him. And don’t assume he’s one dimensional: that would be unfair both to the writers and to Phillips’s nuanced performance. There are moments of stress and hurt that flicker across his face so quickly you’d almost miss them if you weren’t looking. (For example, in the third-to-last episode had a moment that was so stunningly subtle that I actually paused the show— “There,” I remember saying. “Look. He can’t imagine the pain of Malcolm getting there first.”) He’s a scholar in hiding his own self-interest. He has poured all of his love into people who for countless reasons either can’t give it back or aren’t as good at being open with love as he is.

I have two more Prodigal Sondays. In fact, tonight is one. But I wanted to start saying my goodbye to Gil a little early, because I know by the time the credits roll next Wednesday, I’m going to be wrecked. I had to say goodbye early because I needed to say this— no matter what happens, Gil, I saw you step in with Malcolm Bright, the scared kid and the not-much-less-scared man. I saw you watch him grow and try to help him without imposing too much, never really having a name for your place or role. I saw you bury your love in verbs and actions. I saw you love Jess from afar, saw the look in your eyes that told me how you loved Jackie even though she’s been gone since the “action” of the show began. I saw you love JT when he faced racial injustice, and I saw you love Dani when she needed someone to pull her back on a case that looked a little too familiar to you.

I couldn’t let all that love go unacknowledged. So? Gil Arroyo? You don’t have to say this back— but I love you. Thanks for the 33 episodes we spent together. And no, I’m not really ready to say goodbye, but if I’ve learned anything from graduations and the years falling off the calendar in my stepdaughter’s life? I wouldn’t have been ready in 33 years— not with a character who loves in a way that is so familiar, so natural to me, I almost didn’t recognize it as unique.

Thank you for putting into words how so many of us felt about Gil Arroyo and The Prodigal Son. It was sad to lose such a great series 😢